Stewardship, Diaspora, and the Legacy of Koyo Kouoh

American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA and the quiet labor of building cultural connections without simplification.

What does cultural care look like when it must move across oceans, histories, and unequal economies, when it must resist the gravitational pull of spectacle, market appetite, and the Western gaze? For those stewarding the work of Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa and its U.S.-based counterpart, American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA, the answer begins with something deceptively simple: respect.

It is a word that surfaces repeatedly in conversation with the organization’s leaders– not as a platitude, but as a governing principle. Respect for artists. Respect for complexity. Respect for the fact that African art does not need translation so much as space.

Founded to support Zeitz MOCAA, the largest museum dedicated to contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora, American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA plays a crucial role in extending the museum’s vision beyond Cape Town while remaining accountable to it. That vision was shaped decisively by Koyo Kouoh, the museum’s former Executive Director and Chief Curator, whose death earlier this year left a profound absence in the global art world. Kouoh did not simply lead Zeitz MOCAA; she gave it moral clarity. Under her leadership, the museum became a site of intellectual rigor and care, committed to African artists telling their own stories– fully, messily, and without apology.

American Friends exists not to dilute that vision for U.S. audiences, but to protect it.

Koyo Kouoh, photo courtesy of American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA

“I think when we talk about cultural care, it really comes down to respect and honor,” says Naledi Khabo, Co-President of American Friends and CEO of the African Tourism Association. “That applies whether you’re talking about art, history, music, fashion– anything that’s being shared.”

Khabo’s background spans tourism, public advocacy, and leadership across sectors, and that perspective shapes how she understands the stakes of cultural export. African culture, she notes, already drives much of global culture, from music and fashion to film and visual art. The question is not whether it will travel, but how.

Naledi Khabo, photo courtesy of American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA

“We talk a lot about African products as exports,” she explains. “So the responsibility becomes: how do we do that in a way that’s thoughtful and full of respect? How do we make sure we’re accountable– to artists, to the art, to the culture itself– and not just chasing opportunity or commercialism?”

That accountability, she emphasizes, is rooted in partnership rather than profit. American Friends’ role is not to frame African art as exotic or consumable, but to support its circulation without flattening it.

“I reject the notion that it’s our responsibility to interpret Africa for the West,” Khabo says plainly. “Our responsibility is to make sure artists can speak for themselves, and that the stories being told reflect the reality that Africa is not a monolith.”

For Roger Ross Williams, an Academy Award–winning filmmaker and founding board member, this work is deeply personal. As an African American artist, his involvement with American Friends is about sustaining a living connection to the continent, not symbolically, but through relationships with artists, studios, and communities.

Roger Ross Williams, photo courtesy of American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA

“Being connected to artists on the continent has been incredibly fulfilling for me,” he says. “It’s about community– the African diaspora across the globe, and being in real conversation with one another.” That conversation often takes place far from institutional walls. Through American Friends–organized art trips to places like Nairobi, Senegal, Uganda, and Rwanda, members engage directly with artists in their own environments.

“To meet artists where they live, in their studios, in their spaces– it’s a powerful thing,” Williams says. “You’re not just looking at finished work. You’re witnessing process.” Process, in fact, is central to how both Zeitz MOCAA and American Friends understand stewardship. Williams recalls the museum’s artist-in-residence program, where an artist’s studio is transformed into a public-facing space within the museum itself.

“You walk through, and you see how the work is made,” he says. “It changes the relationship entirely. It’s not just about the object, it’s about how the artist thinks, how they live with the work as it’s forming.”

That emphasis on lived experience and exchange is echoed by Claire Breukel, Head of American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA and a South African–born curator whose work spans continents and institutions. Breukel worked closely with Kouoh for several years and speaks of her philosophy as one grounded in long-term care rather than transactional support.

“Koyo used to say, ‘People are more important than things,’” Breukel reflects. “It sounds simple, but it guided everything she did.”

That ethos shaped how Zeitz MOCAA approached artists, exhibitions, and supporters alike. Rather than chasing one-off donations or high-visibility moments, Kouoh advocated for sustained commitment– building infrastructure, publishing scholarship, and foregrounding artists who had long been overlooked or underrepresented.

“She was adamant about producing books for every exhibition,” Breukel notes. “Publishing was not an afterthought; it was part of how you make sure the work lives beyond the moment.”

American Friends extends that commitment through programs that materially support artists and cultural workers, including museum fellowships that bring emerging professionals from across the Pan-African world to Cape Town for a year of study and hands-on experience. Fellows work across departments at Zeitz MOCAA while completing postgraduate degrees, emerging equipped not just with credentials, but with institutional fluency.

“We’re training the next generation of museum professionals,” Breukel explains. “That kind of investment changes what’s possible– not just for individuals, but for the field.”

As global institutions grapple with questions of restitution, canon formation, and who gets to steward African cultural heritage, these efforts take on added weight. Khabo speaks candidly about the unfinished work of confronting colonial legacies, from the return of looted artifacts to the persistent imbalance of who controls African narratives.

“There’s still so much colonialism embedded in how African art is held and framed globally,” she says. “We have a responsibility to reshape that, to advocate for African storytelling, African expression, and African art being seen on its own terms.”

For Williams, Kouoh’s greatest gift was the clarity she brought to that responsibility. “When she arrived, the museum was still defining itself,” he recalls. “Koyo gave it purpose. She made it a home, not just a place to view art, but a place to experience artists as people.”

Her passing leaves an absence that cannot be filled, but those who worked alongside her are clear-eyed about what comes next. Legacy, they insist, is not something to preserve in amber. “We don’t honor Koyo by freezing her vision,” Khabo says. “We honor her by extending it.”

Breukel agrees. “Her work taught us that care is not passive. It’s active. It requires commitment, patience, and courage.”

In that sense, American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA is less an auxiliary organization than a continuation– a transatlantic practice of care that insists African art deserves to move through the world without being reduced by it.

Learn more about American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA here.

Footnotes: The Work of Care

Some cultural work resists urgency. It asks for patience, proximity, and attention over time. The practices below echo the philosophy at the heart of American Friends of Zeitz MOCAA and Koyo Kouoh’s vision: that art is not simply presented, but stewarded.

Spaces That Hold Process

RAW Material Company (Dakar): A site where artistic practice, research, and critical thought unfold without pressure toward spectacle.

The Bag Factory (Johannesburg): An artist-led space rooted in experimentation, residencies, and long-term dialogue.

Black Rock Senegal: A residency program offering artists time and distance without demanding a finished outcome.

Writing as Preservation

Zeitz MOCAA exhibition catalogues: Publishing as an extension of care, ensuring that exhibitions live beyond their moment.

Condition Report on Art History in Africa: A reminder that archives are constructed, and that expanding them is ongoing work.

Seeing Work Mid-Formation

Zeitz MOCAA’s artist-in-residence program: Inviting audiences into process rather than only arrival.

Studio visits as methodology: Central to American Friends’ art trips, emphasizing presence over consumption.

Artists Who Refuse Simplification

Otobong Nkanga, Zanele Muholi, Dineo Seshee Bopape, and Santu Mofokeng engage in studio practices that insist on complexity, interiority, and self-definition.

Legacy, Understood Differently

Koyo Kouoh often resisted the idea of legacy as something to be preserved. Instead, she understood it as something that must remain alive — extended, challenged, and carried forward.

Homecomings and Creative Displacement

Going home has a way of rearranging you.

For creatives especially, returning to a childhood house, a familiar neighborhood, or a city you once knew intimately can feel less like a reunion and more like a subtle undoing. The version of yourself that makes the work doesn’t always fit so neatly back into the place that made you.

During the holidays, many people step back into rooms where their earliest instincts were formed– kitchens where hands learned the rhythm of cooking before language, bedrooms where imagination filled in for space, streets that once felt enormous. These places can be grounding. They can also be disorienting. The furniture has changed. The conversations haven’t. The walls remember you differently than you remember yourself.

Creative displacement often lives in this tension. You are no longer who you were when you left, but the place still holds you. For some, that friction sharpens perspective. Old dynamics resurface. Long-held roles reappear. And suddenly the confidence you carry in your work feels more fragile, more exposed.

Yet this dislocation can be generative.

Being temporarily unmoored– out of your routine, out of your usual environment, maybe even a little on edge– forces a different kind of looking. It reminds you that creativity doesn’t only live in studios or schedules. Sometimes it arrives in overheard conversations, in the weight of family history, in the recognition of how far you’ve traveled from the person you once were.

Homecomings ask a particular question: what do you carry with you, and what no longer belongs? They reveal which parts of your creative identity are sturdy enough to move across places, and which were tethered to geography, distance, or solitude.

Not everyone returns home by choice. For some, home has changed irrevocably. For others, it no longer exists in physical form. In those cases, creative displacement is not seasonal but ongoing. Making becomes a way of assembling fragments into something livable.

The holidays amplify this reality, but they don’t create it. They simply place us in closer proximity to the spaces that shaped us, and invite us to notice what still resonates, and what doesn’t.

Perhaps the quiet work of this season isn’t resolution, but recognition. Understanding that creativity, like home, is something we are constantly renegotiating. And that sometimes, stepping back into old spaces helps us see more clearly where we are going next.

image: Alec Soth, Peter's Houseboat, Winona, Minnesota, Photographed in 2002 and printed in 2004, Chromogenic print

Who Gets the Time to Create?

Creative work has always needed one thing more than anything else: time. Not the romantic kind that floats through glossy studio tours, but the real kind– the hours you fight for, protect, and stretch, the hours when your mind is clear enough to make something that didn’t exist before. And in 2025, time has quietly become the true measure of privilege in the creative world.

That’s why the conversation coming out of the UK feels so telling. There’s been a growing chorus of voices pointing out what many already knew: an alarming number of the country’s most visible young artists come from upper-class families. Not because they’re less talented, but because they’re the ones who can afford to spend years experimenting, drifting, refining. They have the safety net to take creative risks while others are working shifts, managing caretaking, or navigating the instability that makes risk impossible. In short, their parents are paying the bills while they are in studio.

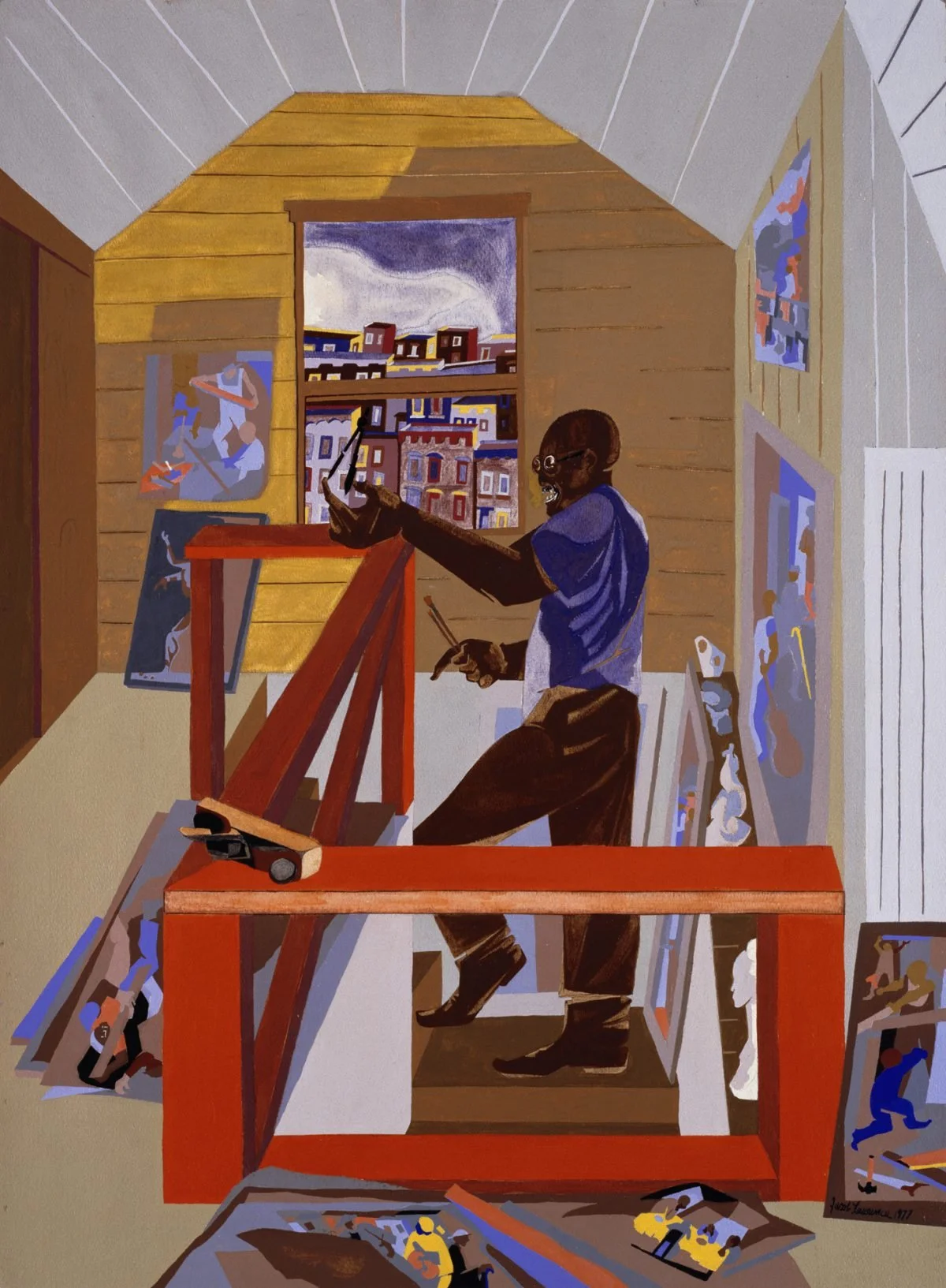

Across the Atlantic, the U.S. amplifies this dynamic. This country hasn’t meaningfully invested in artists at a federal level since the WPA, nearly a century ago, when creative labor was treated as necessary infrastructure. It’s always a bit jarring to be reminded that the government once subsidized the work of some of the giants of American early modern art. Since then, artists have been expected to bootstrap themselves into cultural relevance, often without stability, support, or time. Here, you either inherit spaciousness or you create in the margins of your exhaustion after you clock out.

And yet, this is where the story turns. Because if you listen closely, the most interesting work right now isn’t coming from the people with the most time; it’s coming from the ones who carved it out anyway. Working-class artists, immigrant artists, artists raising families, artists threading creativity through jobs, commutes, and late nights. People whose creative muscles are shaped not by comfort but by constraint, resourcefulness, and lived experience.

The future of culture is already being built from the ground up, by the people who were never invited into the “creative class” conversation. By artists who had to become their own institutions. By communities that have always produced the culture everyone else eventually catches up to, especially Black creatives and other marginalized communities.

But the uncomfortable truth remains: creativity takes time, and time is currently distributed the same way wealth is– unevenly, predictably, and with generational consequences.

So the real question isn’t whether working-class artists exist. They always have.

The question is: what would culture look like if they had the time they deserved?

If time weren’t a luxury item?

If creative risk wasn’t a class privilege?

If the next WPA wasn’t a memory but an intentional, renewed mandate?

Because the next era of creativity is already here– it’s just waiting for the world to make room for it.

image: The Studio, 1977, Jacob Lawrence, Gouache on paper

Instinct, Craft, and the Pursuit of Making

James Galbraith’s work at PostBoy reveals a chef shaped equally by kitchens, ceramics studios, Japanese street stalls, and a lifelong eye for design.

James Galbraith's education was pieced together the way certain artists learn to see– by living inside the work. Cookbooks stacked on the floor. Late nights in Chicago kitchens. Stages spent observing more than speaking. He calls it “stitched together,” but the result is unmistakably whole: a sensibility shaped by craft, curiosity, and an almost architectural attention to detail.

Ask him what influenced him most in those early years, and he doesn’t hesitate. “I have many cookbooks,” he says, “but Homegrown by Matthew Jennings was the most influential for me.” It’s telling: Jennings built his reputation on using place, memory, and restraint as building blocks. Galbraith absorbed that lesson early– that food, at its best, is design.

Now, at PostBoy, the restaurant he co-owns in New Buffalo, Michigan, that design sense shows up everywhere. It’s in the way he builds dishes– crisp, minimal preparations that borrow equally from Japan, South America, and the Great Lakes. It’s in the curve of the dining room, which echoes the classic American diner forms he’s always loved. It’s in the plates themselves, handmade by Myrth Ceramics in a warm, matte palette that makes every dish feel rooted.

Those plates have their own story. “We visited the studios of the ceramicists who made our plates,” he said. “They are very much works of art on their own. Ceramics is something important to me.” At the studio, someone asked if he wanted to try the wheel. “I made a plate on my first try.” He laughs about it, but the moment captures something essential about him– the maker’s instinct, the compulsion to try, touch, build. “The plates are an important part of the presentation and add another layer of creativity,” he said. “They are truly beautiful.”

That pull toward the visual world runs deep. Before PostBoy, Galbraith helped build out three restaurants, giving as much attention to the interiors as to the menu. “I made sure that all three of the restaurants I’ve been involved in have their own specific point of view,” he said. In one, he preserved the historic floors; in another, he chased the clean, graphic curve of a diner. “I’ve always been just as interested in the interiors as the food itself.”

This openness– an eye that moves across disciplines– is part of what makes his work feel alive. Tattoos, for example, gave him one of the core lessons he applies to cooking. “When I was getting the owl tattoo on my chest, I went in with a drawing I made,” he said. “The guy looked at it and came up with a completely different drawing that looked much better than mine. That was the last time I did that.” It taught him trust– in other makers, in the integrity of their craft, in letting expertise lead. “When people make suggestions to the menu, I just accept their feedback and walk away. It’s important to realize that you know what you know, and to do the best you can.”

His respect for process deepened when he visited Japan for the first time earlier this year. “I could see how much respect they have for their country and their process,” he said. “There is a level of pride that runs across everything they do.” He found himself drawn not to the Michelin temples but the tiny food stalls, the places where pride shows up in the smallest gestures. That ethos, intimate, exacting, intentional, hangs over PostBoy.

Still, instinct sits at the center of how he cooks. “There are times when I’m putting together a recipe when I have to rely on instinct,” he said. “When you’ve done a certain amount of eating and cooking, you realize that you don’t need to taste everything that goes into a dish. Your instinct guides you. And that’s where the confidence comes from– being able to trust it.”

What may be most striking about Galbraith, however, is how clearly he sees the boundary between craft and life. He talks about family in the same language he uses for the kitchen: care, precision, and intention. “The different parts of your life are the ‘gardens,’” he told me. “And they all have to be watered and tended to individually to keep them alive.”

That clarity didn’t always come easy. “My daughter was seven or eight before I was the one who took her trick-or-treating for the first time,” he said. “Once I saw how much fun she was having, I stopped working on Halloween night.” The same went for Father’s Day. “I realized I don’t know how many more Father’s Days I’ll have with my own father, so I don’t work on Father’s Day either.” For him, the math is simple: restaurants come and go; the vibrant, most important gardens don’t.

Strip away the openings, the press, the slow build from busboy to one of the region’s defining culinary voices, and what remains is a maker committed to doing his work well. “I’m trying to make sure that I am always doing the best that I can do,” he said. “This is the only real skill set that I have, and it is important to me to always do the best that I can. My father stressed that your reputation is the most important thing you have. That was the most important professional and personal advice I ever received.”

At PostBoy, that reputation is built one plate, one curve, one decision at a time, the quiet accumulation of a life lived looking closely. Not just at food, but at the entire creative world that shapes it.

images: headshot of James Galbraith, and interior and exterior images of PostBoy, courtesy of Gabrielle Sukich. Portrait of Galbraith with co-owner Ben D. Holland, courtesy of Elena Grigore Photography.

Where Creativity Goes When Third Spaces Disappear

Winter is on the horizon, the season that makes every city feel a little smaller. The days shorten, the streets empty faster, and you start to notice what’s missing, especially the spaces that used to hold us. Cafés that felt like a second living room. Bookstores that stayed open late. Community spaces that didn’t require membership, money, or a reservation made three weeks out.

For young creatives, the loss of these places isn’t just inconvenient. It’s structural. It changes the way culture forms and determines whether it forms at all.

There’s a long history of creativity being shaped by rooms that were neither home nor work. Gertrude Stein’s Paris salon was as much a cultural accelerant as the early modernists themselves, a place where Hemingway and Picasso learned each other’s rhythms before influencing each other’s work. Decades later, New York’s Cedar Tavern helped shape the Abstract Expressionists; so much of their mythology comes from the fact that they gathered loudly, messily (the AbEx artist fights are legendary at this point) in the same smoky room. Meanwhile, Black cultural innovation in the mid-20th century unfolded inside barbershops, church basements, record stores, and front porches. These were not merely backdrops. They were incubators.

In Tokyo, kissaten cafés were once the homes of quiet rebellion; a refuge for postwar writers and students who needed somewhere to think. In Kingston, the early sound system culture grew out of makeshift street parties where people gathered not just to dance, but to experiment with sound, engineering, and identity. Even the Bloomsbury Group needed rooms: private homes, gardens, reading circles. Culture has never grown from isolation; it needs the oxygen proximity provides.

When cities lose their third spaces– the places where you don’t have to buy anything to belong– creative communities lose their connective tissue. There’s no soft landing for the young writer who doesn’t yet know if she’s a writer. No place where a teenage photographer can observe how other people move through the world. No table where strangers become collaborators. And without those moments of casual overlap, the path into creative life becomes lonelier, more exclusive, and harder to enter.

This isn’t sepia-toned nostalgia. It’s neuroscience. Creative thinking thrives on environmental stimulation, on subtle cues from other bodies: how someone tilts a book, the way a stranger reacts to a line in their notebook, the shared energy of collective focus. Serendipity isn’t romantic; it becomes its own infrastructure.

Today, that infrastructure is fragile. Rising rents push out independent spaces. Corporate coffee chains turn every room into sterile laptop farms. Cities that once had rich creative subcultures now feel flattened, optimized, and scrubbed of friction. And for emerging creatives, especially those without family wealth, connections, or confidence, the lack of a place to simply be is not a small loss. It’s a slowly unfolding cultural one.

Because third spaces are where people first try on their creative selves. They’re where early drafts are written, where ideas are exchanged, where someone overhears a conversation that unlocks something inside them. They’re where a person begins to feel part of something larger– a community, a scene, a lineage. Without them, young creatives are asked to start in isolation, to build a voice without an audience, to find a path without the gentle hum of others doing the same. Remember in school when the preppy girl came back after summer vacation as a Goth? Chances are, she first encountered alt people at a third space, probably the mall.

But something else is happening, too: new third spaces are slowly emerging, born out of necessity. Pop-up salons in someone’s living room. Artist-led bookstores that double as gathering spots. Small-town wine shops hosting poetry readings. Restaurants with communal tables that quietly become the meeting place for a new generation. Even tiny cafés in coastal towns– the kind with three tables and a counter– are once again turning into creative sanctuaries, just because they allow people to stay awhile and be.

The question now isn’t whether third spaces matter. It’s how we cultivate them, and how we protect them. How we make room for young creatives who need somewhere to land, somewhere to linger, somewhere to feel themselves forming. A city without places to gather is a city without cultural memory. A creative ecosystem without shared rooms becomes an economy of emotionally detached individuals rather than a potentially vibrant collective imagination.

If there is any hope for where culture goes next, it’s in rebuilding the rooms where people can see themselves reflected in one another. Not perfectly, not permanently, but enough to feel possible.

At Bureau, we have been watching this shift closely. It feels aligned with the things we care about: culture as conversation, community as catalyst. And as we imagine the next chapter of what Bureau can be, including intimate, human-scaled gatherings and events in the months ahead, our goal is to create rooms that honor that lineage. Not loud, not overproduced. Just intentional spaces where creative people can land, talk, think, and maybe leave with a spark and new connections they didn’t walk in with.

Because when you lose third spaces, you don’t just lose ambience. You lose the accidental, and often lovely collisions that shape a life. You lose the table where ideas sharpen. The booth where a story begins. The barstool where someone tells you the thing you needed to hear. Culture has never come from isolation. It comes from shared air.

And so the question isn’t just where we gather now. It’s what we might create together once we finally do.

image: Robert Capa | Cafe de Flore, 1950s

The Way We Gather

As the holiday season slowly pulls us back toward dining rooms, long flights home, and the familiar choreography of shared meals, the table becomes an emotional anchor, for better or for worse. Even people who claim they “don’t really cook” suddenly start bookmarking recipes. Those who live far from family begin negotiating calendars and steeling themselves for fraught conversations. Friends take quiet note of who might need an invitation this year. The table becomes more than a place to eat; it becomes a moment to decide who we are to each other.

A table is one of the most ordinary objects in our lives, yet it’s where some of the most essential human rituals unfold. Meals turn into memory. Seating becomes a signal. The way we gather, the way we arrange plates, pour drinks (and more drinks), pass dishes — is a cultural language all its own, shaped by place, belief, migration, and the invisible politics of intimacy and connection.

Across cultures, the table becomes a stage with distinct lighting and a signature setting.

In Japan, meals are built from closeness to the ground. Tatami mats, low tables, and the deliberate placement of dishes create a hushed reverence. Generosity shows up in small gestures, such as pouring tea for someone else first, or pausing before the first bite.

In Morocco, everything radiates from the center. A communal dish anchors the table, and bread becomes both utensil and invitation. Eating with your hands is not only sensual; it’s a kind of proximity, a rhythm shared among the guests around the table.

Italy operates on an entirely different clock. Meals stretch. Courses multiply. Conversations become louder and more alive. The table becomes an engine to supercharge storytelling, with arguments, laughter, and affection all swirling around the same surface.

In Korea, the table becomes a landscape. Banchan plates build a world of contrasts: fermented, crisp, spicy, soothing. It’s a philosophy brought to vivid life in flavor.

Scandinavian tables lean into quiet, modern clarity. Wood, ceramic, soft candlelight. Hospitality is communicated not through excess but through intention, an exercise in how little it takes to make someone feel considered.

Across the American South, the table becomes an inheritance. Recipes, rituals, and mismatched heirloom dishes reflect a kind of hospitality that isn’t performed; it’s lived. And within Southern Black food culture, that inheritance carries a particular weight, a cuisine shaped by resilience, land, memory, and improvisation. The table becomes a site of both survival and celebration, where generations have preserved flavor as a form of history and offered hospitality as both resistance and love. The best part? There is always room for one more.

And across the Middle East, abundance doubles as welcome. Platters refill themselves, generosity becomes the dominant season, and the table tells you: here, you are held.

What holds these scenes together is a simple truth: gathering isn’t really about food. It’s about the architecture around it; the emotional design of how we come together, listen, celebrate, and (hopefully) mend. The table becomes a blueprint for how culture is built and rebuilt daily.

Footnotes: Books & Cookbooks Worth Spending Time With

If you’re looking to deepen your own rituals or explore the ways others shape theirs, these books offer much more than recipes. They map out philosophies, histories, and the intimate logic of how we nourish each other.

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat by Samin Nosrat. A sensory atlas of global flavor and an exploration of the craft behind it.

The Nordic Cookbook by Magnus Nilsson. An impressively expansive look at the landscapes and ethos that define Nordic food culture.

The Soul of a Chef by Michael Ruhlman. A behind-the-scenes portrait of naked ambition, obsession, and craft.

Arabesque: A Taste of Morocco, Turkey, and Lebanon by Claudia Roden. A deeply rooted look at Middle Eastern hospitality and history.

Pasta Grannies by Vicky Bennison. Generational knowledge, regional traditions, and the intimacy of cooking as inheritance.

Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking, by Toni Tipton-Martin. A landmark celebration of Southern Black culinary tradition, technique, and legacy.

The Noise Outside

When the world grows unbearably loud, the act of creating can feel almost defiant. Every era has its noise, whether political, cultural, or existential, and still, artists have returned to the page, the canvas, and the lens to search for coherence in the chaos.

There are stretches of time when the world grows so loud it feels impossible to think, much less to create. There is an undercurrent of constant tension-news, noise, and seemingly endless suffering. Even silence feels politicized. In these moments, the creative act can seem indulgent and out of step with urgency. And yet, time and again, artists have found their most enduring voice in the midst of chaos. Creativity has always found a way to breathe under pressure.

In Europe in the years leading up to World War II, creation was inseparable from crisis. German artist Käthe Kollwitz’s stark etchings captured the crushing weight of grief before language could name it. Her lines– tender, brutal, and human– stood as a witness to loss in the shadow of war. In Paris, Picasso’s Guernica transformed the horror of the Spanish Civil War into a universally resonant monument to suffering, an image that transcended propaganda through its sheer emotional charge. Around him, the Surrealists—Dalí, Ernst, Tanguy—employed dream logic to capture a world coming apart at its seams. Their art was not escapism, but translation: an attempt to represent a collective psychic rupture when reason no longer sufficed, and no one knew where to turn to make sense of it all.

Decades later, in the thick of the Civil Rights movement, James Baldwin wrote The Fire Next Time, holding up a mirror to America as its streets burned. Nina Simone set that same urgency to sound, turning fury and heartbreak into melody. And halfway around the world, in postwar Japan, photographer Shōmei Tōmatsu found intimacy in the ruins, documenting a country in the process of rebuilding its sense of self. The same could be said of artists working through colonial and postcolonial transitions, such as Fela Kuti’s Lagos and Ernest Cole’s South Africa, where sound and image became survival.

What ties these creators together is not simply their response to turmoil, but their insistence on presence within it. To create during unrest is not necessarily to make work about that unrest. Sometimes it means fiercely protecting beauty in a moment that seeks to destroy it. During World War II, Georgia O’Keeffe painted desert horizons that seemed untouched by conflict, yet her restraint was a quiet protest—a belief that attention and beauty still mattered. Toni Morrison once said that “the function of freedom is to free someone else.” Writing, for her, was an act of reclamation, a way of making sense of a world that stubbornly refused coherence.

Even now, artists like Carrie Mae Weems, Toyin Ojih Odutola, and El Anatsui extend this lineage, transforming social fracture into something both visual and meditative. Their work reminds us that art is not merely a reaction; it’s a reassembly. It asks us to see, to listen, to slow down in the face of the relentless.

There’s a temptation to believe that creativity requires calm, that inspiration only thrives in peace. But the truth may be the opposite. The artist’s role has always been to listen differently—to capture the pulse of a world racing forward too fast and translate its chaos into something recognizably human. Maybe the challenge now isn’t to block out the noise, but to reframe it.

The world has rarely been quiet. But creation, in its most essential form, is an act of coherence. Whether in etching, in song, or in the sweep of a brushstroke, art has always found a way to make meaning in the static and to build a moment of stillness inside the storm.

Above: Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child, 1903, Line etching, drypoint, sandpaper, and soft ground with imprint of ribbed laid paper and Ziegler's transfer paper.

Interview: L’Oreal Thompson Payton, Journalist, Writer, Owner– Zora’s Place

From the moment she first pressed pencil to paper—at three years old, a spiral notebook balanced on her knees—L’Oreal Thompson Payton understood that language could be a place to live. Over time, that instinct became a powerful compass. As a writer, journalist, and now the founder of Zora’s Place– Evanston, Illinois’ first Black feminist bookstore, she has moved through the world with a steady devotion to representation: writing herself into stories long before she ever saw herself reflected.

Zora’s Place arrives at a moment when publishing’s promises feel suspended; when doors crack open only to narrow again, and whose stories matter is still too often negotiated. Named in homage to author Zora Neale Hurston, the space is deeply intentional. Yet calling it a bookstore feels incomplete. It’s a community hub, a third space, a soft landing for those who have too often been asked to make do without one. Thompson Payton’s curatorial lens extends beyond the page: Black women-owned products, wellness rituals, gatherings that carry joy and protest in the same breath.

In our conversation, Thompson Payton reflects on claiming authorship in an industry that rarely makes room, on kicking doors wider when they shift even a little, and on building a space where Black women are centered without apology. More than anything, she reminds us that community—real, embodied, in-the-room community—is no longer optional. It’s the core assignment.

You've built a life around language as a writer, editor, and now through Zora's Place. How would you describe your earliest relationship with writing, and what has stayed constant about it over time?

I love the wording of that question. In my first book, Stop Waiting for Perfect, in one of the earlier chapters, there is a picture of me about three and a half, sitting on the sofa with my sister, who's probably about six months or so at the time, and I have this spiral-bound notebook, probably wide-ruled, in my lap. And I don't know what I was writing that day. It kind of looks like I'm interviewing her, but she's like six months old and can't talk. And I mean, I'm three, I can't write, but that is the earliest memory I have about writing. When I was six, I wrote this book about dinosaurs in outer space. I've always had my nose in a book since very early on.

“I think even at a young age… I was writing stories to write myself in, to write that representation that I didn’t see.”

There were times when we were in the car driving home from somewhere, and I would use the headlights from the car behind us to read my book. Books were always a place to escape. And even as a child, I recognized the lack of diversity and representation in a lot of those books at the time. I love Berenstain Bears. I loved Sweet Valley High, Goosebumps. I loved all of those, and didn't see little Black girls in those stories. And so I think even at a young age, I don't think it was necessarily a conscious thing, but I was writing stories to write myself in, to write that representation that I didn't see.

And that's been the through line and everything that I've done, from elementary years to high school. Through being the editor-in-chief of the student newspaper, through the internships I've had and other writing-specific roles in newsrooms and even nonprofits, and now as an author, representation has always been top of mind. I wanted to be editor-in-chief of a teen magazine because I didn't want any other little Black girls to feel the way that I did, which was literally praying to God to make me white.

What was the spark that led you to create Zora's Place? Did it begin as a response to something missing in the literary world or as a natural extension of your own creative community?

A little bit of both. So in 2019, a couple of friends and I were in a book club together, and I used the term book club very loosely, because it was kind of a very much BYO book club where we read different books, and then we just met on Zoom to talk about it.

“Zora’s Place is more than a bookstore. It is meant to be a community hub.”

I wasn't even back in full-time journalism yet. I was still in nonprofit PR and just putting the idea on the back burner. And since then, since becoming an author myself, frequenting the independent bookstores that we have here in Chicago– I love Call and Response down in Hyde Park. Courtney, the owner, has been an amazing resource for me during the process of opening my own store, and I believe Evanston deserves this, too. There weren't any Black-owned bookstores. I didn't want to drive 45 minutes to Hyde Park every time I wanted to support a Black woman-owned bookstore. Being the firstborn daughter, an overachieving millennial like that I am, I decided that I should do something about that.

The crowdfunding campaign took off, and now, especially in this moment in time and this political climate, I tell everyone that Zora's Place is more than a bookstore. It is meant to be a community hub. It’s rooted within the Aux Wellness Collective that supports the mental, physical, financial, spiritual, and emotional health of everyone, but especially Black women.

And I think though, as a Black woman author myself and knowing from publishing how we are often pushed to the side, I was like, no. If I'm gonna do this, I'm gonna stand 10 toes down and make this about Black women. Period. And so 99.9% of our books are written by Black women. There are a couple of children's books written by a few good men, because our little boys need to have books that feature them, too.

And then, in naming it after Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes are Watching God is my favorite book of all time. Zora's really a pioneer in her own right. And so I wanted this to pay homage to her. And even beyond the books, all of the sideline items that we have, the scrubs and the nail polish and the puzzles, are all Black women entrepreneurs. Half of whom are local to the Chicagoland area. So everything is very intentional– when you come in here, there's a peace of mind of knowing that you are supporting a Black woman-owned business.

The publishing industry has changed in recent years. Shrinking opportunities, fewer editors of color, and a shifting idea of what's considered marketable. From your perspective, what are the forces shaping that landscape right now?

There was a blip in 2020. Of course, we all know what happened in the summer of 2020. The racial reckoning also happened to be when I signed with my previous agent. And I like to think that is because my book is good and I'm a great writer and all of those things. I believe that that is true, and there was a moment in time where across industries and publishing especially, I think people were like, “Oh my gosh, we need diverse voices.” And so everyone was rushing out to find their Black author, right?

I do think that two things can be true. And as an author, I don't want to take advantage of that, right? I didn't give myself the book deal or sign myself to an agency. When the door opens an inch, I'm gonna kick it down and step all the way in, which is what I have done.

When I was shopping around my infertility memoir, I mutually parted ways with my previous agent because she wasn't sure that it would sell. There were a lot of naysayers because memoir itself is a hard category to break into. And then I think as a Black woman, especially, unless you're a celebrity or public figure, there were a lot of discouraging notes from the people in the industry. And the thing about me, though, is I'm a Scorpio. If you tell me that I can't do something, I'm gonna make it my life's mission to prove you wrong.

There’s a long history of trying to minimize, reframe, or altogether erase Black stories in publishing and media. How do you see your work, both in your writing and with Zora's place, as engaging with this moment in time?

Yeah, no, you're not ignoring us. That was very intentional, too, in the title of my memoir. So for Infertile Black Girl (Payton Thompson’s in-progress memoir about her experience with infertility), there were two original titles that I was working through, one of which was “Infertile Ground”. When people say they hear the “voice of God”, I feel like mine has always been these kinds of whispers and nudges– and the voice that day was: “Infertile Black Girl”. And that was it– because that says everything.

My experience is unique, going through infertility as a Black woman. Wellness in general is a very white space. By naming that and not shying away from it, that means everything to me. It all goes back to representation with me. And there are women that I've met in different support groups, other Black women who've shared the same sentiment about infertility on its own, which is already kind of isolating. And then, when you throw being someone from a marginalized identity on top of that. The isolation just compounds.

Community is a through-line in your work, not just who you write for, but who you create with. What does community mean to you in this moment?

Community is everything, especially in this moment in time. I had a hunch after last year's election that community was going to be even more important. And that was really going to be a theme in 2025. And especially in-person community, I found that in every single group that I'm talking to, people are craving that community and connection.

That's why on the website and every time I talk about Zora's Place, I say it’s more than the bookstore– it’s also a community space because we don't have a lot of third spaces. I want this to be a space where people feel comfortable coming here to study or just have a quiet place to be. At our soft opening, someone from the community bought a book, and she asked if it was okay if she sat and read. Of course, I said yes– that's what it's there for.

I want to create a Black feminist book club. I want to create a Black romance book club. This is why we have a romance section as well, because that is also revolutionary. Black Romance is a form of protest. And so it's very intentional. And the products that we have– having the scrubs, the candles, the soaps, and the nail polish, all of that is part of your health and wellness and self-care, and making time for yourself as well. So, I feel now, and for the foreseeable future, it is our number one charge.

Learn more about L’Oreal and her work here, and Zora’s Place here.

Portrait of L’Oreal Thompson Payton by Joerg Metzner & images of Zora’s Place by EE Bauer Photography

Footnotes: A Brief History of Black Women & Print Culture

Black women have always built literary ecosystems when existing ones refused them. Their publishing, printing, and distributing have been less about capital and more about survival, memory, and community.

Kitchen Table Press (1980–1996)

Founded by Barbara Smith and Audre Lorde, Kitchen Table became an urgent corrective to the white feminist publishing landscape. It didn’t just publish books — it published voice, making space for women of color to speak in their own language, on their own terms. It was understood that representation wasn’t a luxury; it was infrastructure.

Black Feminist Bookstores of the 1970s–90s

Spaces like Sisterwrite and Umoja Bookstore served as literal and figurative shelter. They were hubs for study groups, food drives, childcare swaps, and quiet resistance. Long before algorithms, these spaces curated the canon by hand, offering the kind of hyperlocal curation streaming culture can’t touch.

The Harlem Salons

In the 1920s, living rooms became publishing houses. Zora Neale Hurston, Jessie Redmon Fauset, and Georgia Douglas Johnson circulated manuscripts, shared edits, and built professional networks. These salons transformed domestic space into a cultural engine, insisting that Black women’s intellect was worthy of architecture.

Independent presses of the 2000s

As conglomerates grew risk-averse, Black women responded by launching small presses, chapbooks, zines, and community-run imprints. Their work wasn’t “niche”; it was archival, documenting the lives the market shrugged at. Many of these projects became primary sources in today’s scholarship.

Across every decade, the pattern holds: when the door is closed, Black women build their own rooms, invite others in, and leave the lights on. The lineage is less linear and more like a constellation: bright, scattered, and impossible to forget once you’ve seen it.

Zora’s Place doesn’t imitate that tradition; it extends it– intentionally, with its own focus. And with the same belief: that literature isn’t merely consumed, it’s lived, together.

The Quiet Behind the Ideas

Our current moment prizes speed, visibility, and relentless production. The idea of rest has become almost radical. The rhythm of the world insists on acceleration — more content (the clock has to be ticking on this word by now…), more noise, more urgency. Even the creative fields that once prided themselves on introspection have been swept into a cycle of constant output. The artist’s studio has become a livestream, the writer’s solitude a branded productivity tip. To slow down now feels almost countercultural.

But across disciplines, a quiet resistance is forming. One that values slowness not as evidence of lack of ambition, but as an act of preservation. Ceramicists allowing their materials to dictate the pace. Musicians rediscovering silences as composition. Designers moving off the Fashion Week calendar and reclaiming the space and time to concept collections on their own terms. Writers embracing revision not as delay but as devotion. But what if doing less isn’t laziness? What if it’s a quicker path to precision?

Creative rest isn’t the same as withdrawal. It’s not about disappearance or disengagement, but about turning inward long enough to remember why you make things in the first place. The world doesn’t stop pressing in, but rest becomes a way to meet it with more clarity, a kind of interior recalibration. In that stillness, attention sharpens. Work deepens. The noise recedes just enough to hear yourself think again.

This call for rest also sits inside a larger, more fraught cultural moment. The political climate has rarely felt heavier — acute anxiety, injustice, war, and environmental dread have turned collective fatigue into a kind of shared language. The constant scrolling between crisis and performance erodes focus; it’s difficult to feel imaginative when the ground beneath us feels unstable and increasingly porous. For many, rest is not only restorative but necessary for survival, a refusal to let exhaustion define one’s relationship to the world.

Slowing down is a form of intelligence. To resist speed for the sake of speed is to protect nuance, to hold on to complexity when the world demands shallow simplicity. The creative process is a cycle. It’s expansion and contraction, output and retreat. The most resonant ideas often emerge not in the rush of deadlines but in the quiet little pockets between them, when our mind is unguarded enough to wander, and maybe even when we are thinking of something else entirely.

As we move through another season that feels both accelerated and uncertain, there’s value in remembering that to pause is not to lose momentum, it’s to honor process. Rest is the space where perspective realigns, where beauty has time to surface and take a breath. Perhaps the point isn’t to keep up at all, but to keep faith with the work itself: deliberate and unbothered by pace.

Above: Danielle McKinney, Sandman, 2024, oil on linen

Field Notes: Five Cultural Events Defining Fall 2025

Summer has faded, and the creative world has sharpened its focus. This season's calendar is stacked with moments that bridge beauty, intellectual stimulation, and intimacy. Here are five events that caught our eye, and might be worth a journey of your own.

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.L.: Celebrating Four Decades of Innovation & Collaboration

Any survey of post-war American art would be woefully incomplete without Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008). Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles presents Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.L.: Celebrating Four Decades of Innovation & Collaboration, a sweeping centennial exhibition of Robert Rauschenberg’s storied printmaking practice, honoring the artist’s enduring dialogue with the print workshop he first joined in 1967. The artists’ first print edition with Gemini G.E.L., titled Booster, was originally intended to include one single, full-body x-ray, conceived as a “self-portrait of inner man”. Obviously, this was an impossible feat to produce, so the artist and Gemini’s founders decided to scan the artist’s body in six sections to complete the image.

Drawing upon a meticulous curatorial selection of emblematic works—such as Sky Garden from the Stoned Moon series—the exhibition explores the space between paper, ink, found materials, and photographic imagery, evoking Rauschenberg’s restless impulse to expand the expressive reach of print media.

The Los Angeles Gemini G.E.L. exhibit (running through December 19th, 2025 ) is a companion exhibition to Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl in New York City, with that on view until December 20th, 2025. Both presentations mark the centennial of Rauschenberg’s birth and shine an important light on the 40-year relationship between one of the giants of 20th-century art and the publisher, artists’ workshop, and gallery. geminigel.com

Above: Robert Rauschenberg, 'Booster,' 1967, 5-color lithograph & screenprint,72" x 35 1/2", Edition of 3

38th Tokyo International Film Festival

The 38th Tokyo International Film Festival unfolds in several cinemas across Hibiya, Marunouchi, Yurakucho, and Ginza. TIFF continues to serve as Japan’s preeminent gateway to world cinema, offering a thoughtfully edited mix of gala premieres, competition films, and regional showcases.

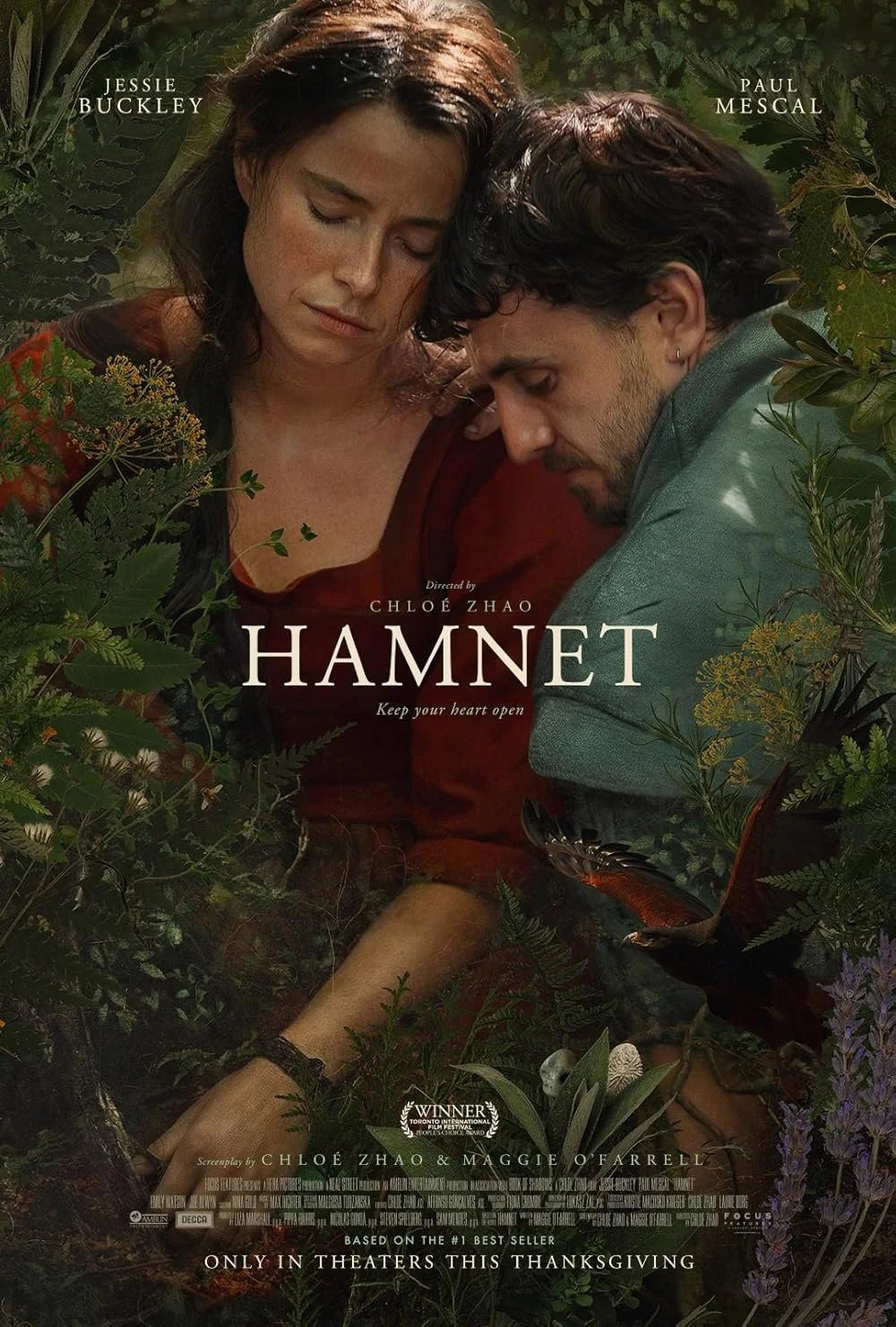

This year’s opening film is Climbing for Life (Junji Sakamoto), and the festival will conclude with Hamnet by Chloé Zhao—framing a boundary-crossing arc between Japanese auteur cinema and global storytelling. As filmmakers, critics, and cinephiles gather, the festival reaffirms its dual role: as a showcase of cinematic excellence and as a hub for cultural diplomacy, creative risk-taking, and film industry renewal. From October 27 to November 5, 2025.

Leslie Hewitt: Achromatic Scales

Leslie Hewitt: Achromatic Scales, the first U.S. exhibition to bring together three of the artist’s ongoing series—Riffs on Real Time, Chromatic Grounds, and Riffs on Real Time with Ground– is now on view at The Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach. Through a carefully calibrated orchestration of layered photographic images (including personal snapshots of family and friends), archival ephemera, and abstract photograms, Hewitt probes how images inhabit time, memory, and space.

Hewitt references Black literary touchstones and post-Civil Rights era pop culture, while adding her voice to art historical traditions, such as still life, minimalism, and conceptualism. With Hewitt serving concurrently as the Norton’s 2025 Artist-in-Residence, the show deepens its resonance by intertwining studio practice with public engagement, offering a rare opportunity to experience new works and evolving ideas in tandem. On view through February 22, 2026. norton.org

Above: Riffs on Real Time with Ground (Green Mesh), 2017, Digital chromogenic print, silver gelatin print, with custom wood frame, Unique, 41 x 91 in. (104.1 x 231.1 cm). Courtesy of the Artist and Perrotin. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarell

Frankfurter Buchmesse 2025

Messe Frankfurt hosts the annual Frankfurter Buchmesse, the premier gathering for the global publishing community, a dense intersection of ideas, rights, and cultural exchange. This year’s edition underscores its evolving mission as a bridge between the written word and film/streaming media, with Book-to-Screen Day spotlighting adaptation, cross-industry partnerships, and narrative translation across forms. With curated author programs and a robust hybrid platform, Frankfurt 2025 highlights the ever-evolving terrain where text, image, voice, and screen converge. From October 15 to October 19, 2025. buchmesse.de

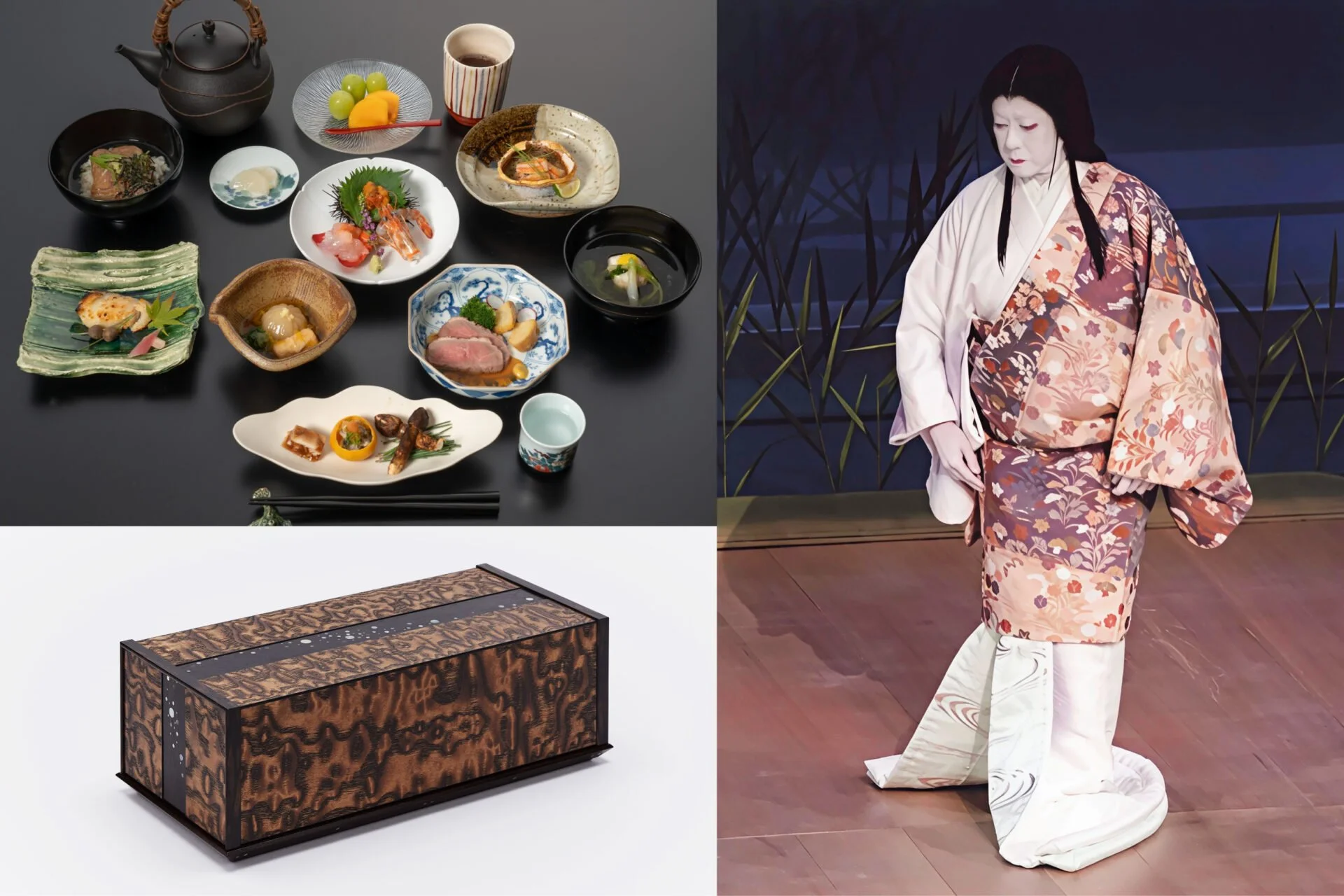

Kōgei Dining 202

In November, the MOA Museum of Art in Atami hosts Kōgei Dining 2025, an immersive celebration of traditional Japanese craftsmanship (“工芸“ or Kōgei), cuisine, and performance. Over five days, guests dine on seasonal dishes served on tableware crafted by Living National Treasures and master artisans, with each piece a quiet collaboration between maker and meal.

The experience extends beyond the table, with daily artist talks exploring the philosophy and process behind Kōgei, and intimate Buyō performances by Bando Tamasaburo on the museum’s Noh stage. Kōgei Dining is an act of reverence for the handmade, the well-prepared, and the fleeting beauty of a shared moment. From November 15th to 19th, 2025. moaart.or.jp

Additional photos courtesy of Tokyo Film Festival, Frankfurter Buchmesse, & MOA Museum of Art

The Transient Table: Food as Performance Art

Food has always been a transient art form. It’s made in a moment, savored in another, leaving only memory and story to hold it firmly in place. The impermanence is where the power of food lies. A meal is fleeting, but its impact can ripple far beyond the table, shaping how we see culture, creativity, and most importantly, community.

Increasingly, chefs and artists are experimenting with the dining experience itself, transforming meals into performances, provocations, and poetry. They are dinners as we know them, but they are also conceived as living works of art, where what’s on the plate is inseparable from the atmosphere, the staging, and the intent.

In London, Bompas & Parr have transformed food into a fairy tale-coded, multi-sensory theater experience. Known for their whimsical installations– think immersive jelly banquets, a breathable gin cloud, or a glow-in-the-dark ice cream parlor– the duo create experiences that blur the line between gastronomy and spectacle. Their work asks diners to reconsider what consumption even means, proving that food can be just as radical a medium as paint or marble. The current situationship between fashion and food has reached Bompas & Parr, with a recent campaign for the August 2025 launch of Gucci’s new GG Marmont handbag. The accessory reimagined as high-concept gelatin.

If you ever wanted to dine en plein air, in the midst of something resembling a Robert Smithson earthworks piece, there’s Jim Denevan. Denevan’s Outstanding in the Field tour has transformed landscapes into dining rooms for more than two decades. Long, meandering tables stretch through orchards and farms, sometimes bending to echo the natural contours of the land. Guests are invited to share dishes sourced from the very ground beneath their feet, often without knowing the menu until the plates appear. The table itself becomes a sculpture, the land a quiet collaborator, the meal an ode to impermanence.

Other expressions are decidedly more intimate, like Chynna Banner’s Tomboy Supper Club in Seattle. Born from her apartment kitchen and now unfolding in pop-up spaces, Banner’s dinners reinterpret Filipino food through the lens of identity, third-culture experience, and belonging. They are gatherings where the menu shifts with each event, designed not just to be eaten but to provoke connection through fermentations, playful reinterpretations, and allergy-friendly adaptations that mirror the fluidity of modern heritage. The glow of her dinners is less about polish than atmosphere: flickering candlelight, crowded tables, laughter caught in photographs that somehow feel nostalgic.

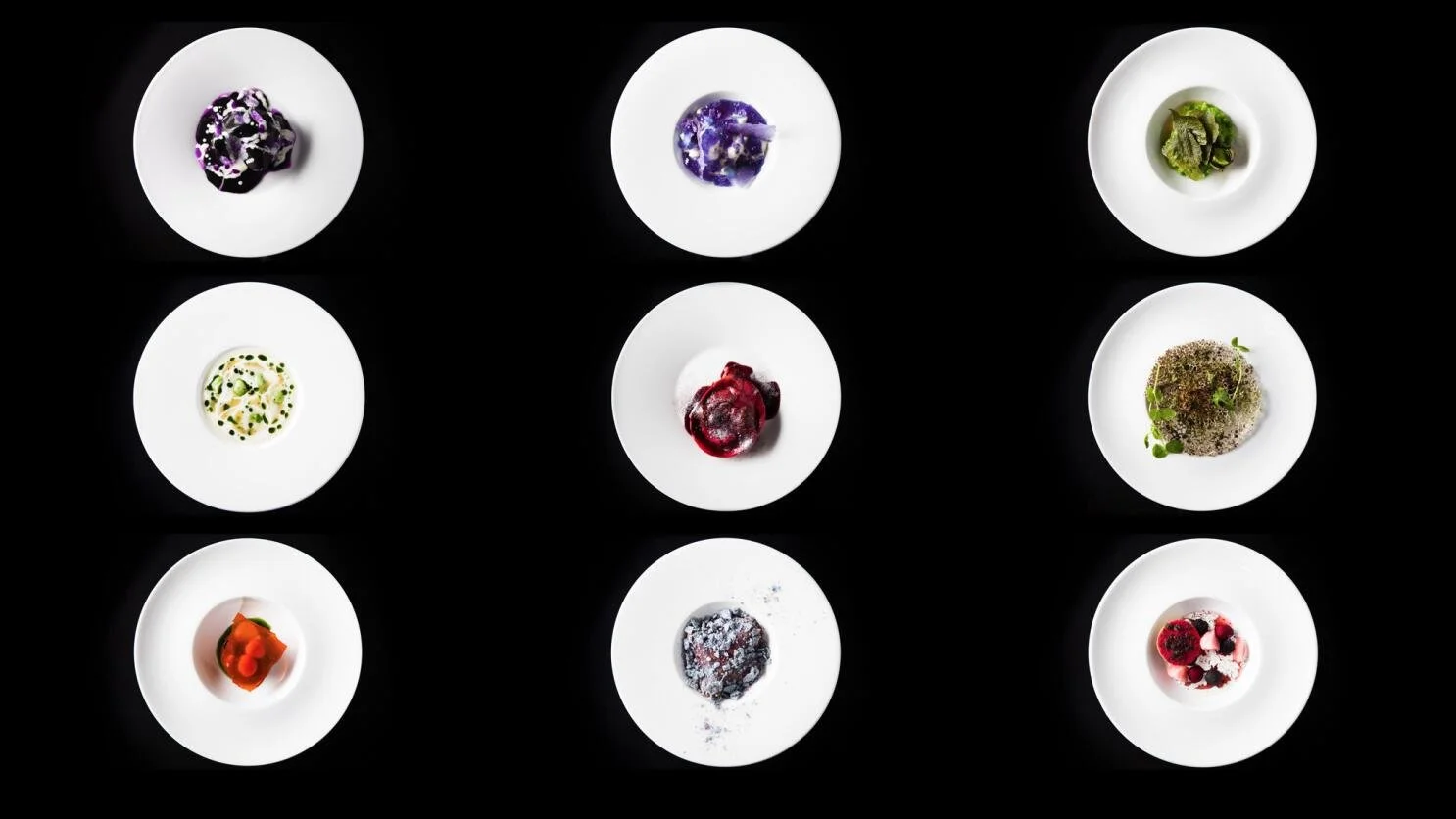

An honorable mention falls into the category of projects that lean fully into art and the grandeur of its legacy institutions. In 2016, Craig Thornton’s Wolvesmouth: Taxa at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles transformed the gallery into an immersive dining space where sculptural installations, sound, and light were as crucial an element as the food itself. Plates emerged as part of a larger visual and sensory metaphor, with purple-skinned dumplings placed against sculptural backdrops, menus intertwined with shifting light. Thornton’s dinners were less about satiation than sensation, existing somewhere between performance and ritual, made meaningful because they were never meant to last.

The connective tissue uniting these experiences is the insistence that impermanence itself is the art form. When meals are relentlessly photographed, shared, and stored for digital eternity, these happenings privilege in-the-moment presence over permanence. They resist documentation and instead reward memory, asking guests to experience food as something fleeting, embodied, and unrepeatable.

These dinners matter because they remind us that creativity often thrives in the momentary, passing much too quickly for us to grab a phone to capture. A table set in a field, a culturally rich supper club hidden in an apartment, a collaboration that flickers for a single night, an art installation that feeds you as much as it disorients you—each reveals how the act of eating can be transformed into something poetic and temporary. Sometimes the most radical thing we can do with flavor is to let it disappear.

Photos courtesy of Bompas & Parr, Jim Denevan/Outstanding in the Field, Tomboy Supper Club, and MOCA Los Angeles

What Agnes Gund Understood About the Power of Art

While many art collectors set about building empires of ownership, Agnes Gund spent her life building bridges. Gund, affectionately known as “Aggie” by those who were close to her, instinctively knew that collecting is not simply about acquiring beauty, but about widening the aperture of who gets to be seen, heard, remembered, and valued.

Before her death on September 18th at the age of 87, Gund pulled the levers of her privilege and resources to support women, artists of color, and those working beyond the narrow perimeters of the mainstream art world. Her storied collection was an expansive survey of modern and contemporary art, broadcasting a vision of art as a more democratic space.

The painting you see above played a pivotal role in shaping Gund’s place as a powerful changemaker in the art space. In 2017, Gund decided to sell Roy Lichtenstein’s 1962 Masterpiece for $165 million, making it one of the most expensive artworks ever sold by a living collector.

But instead of banking the windfall, she used it to seed the launch of the Art for Justice Fund, an initiative dedicated to dismantling mass incarceration in the U.S. During its run (the organization closed its doors in 2023), the fund granted well over $100 million to community-led organizations and artists who are reimagining a more equitable justice system. With that single act, Gund proved that art can have power beyond the walls of a museum.

Her vision extended beyond philanthropy. She spent her life pushing institutions to be more inclusive, whether through her longtime role at the Museum of Modern Art, her work funding scholarships for young artists, or her tireless insistence on acquisitions that expand on the narratives that museums share with the world. She saw art as an active responsibility, not a passive blue-chip luxury.

Gund’s legacy is multi-layered and is sure to be explored in the coming weeks and months, with her influence felt not just in the halls of MoMA, but in communities around the country. She reminds us that creativity underpins a fully realized society.

Suppose we want a better society– one that is more compassionate, more intellectually aware, and more connected. In that case, it’s important to realize that the path runs straight through artists’ studios, restaurant kitchens, performance stages, and the solitary quiet of writers’ rooms. Agnes Gund knew that art was not separate from the realities of our world, but deeply entwined with them.

Footnotes on Collecting Art

This edition of Bureau Footnotes explores the art of building a meaningful collection, featuring Yolonda Ross and her focus on Black and Brown artists. Discover insights into her collecting philosophy and the artists who inspire her work.

One of the first elements to keep in mind when starting an art collection is cultivating a solid idea of what kind of art you want to collect and why. Yolonda Ross’ art collection centers the work of Black and Brown artists, and she has slowly built a collection that participates in the ongoing conversation about race and identity. Click below to learn more about some of the artists in her collection.

Derek Fordjour

Derek Fordjour, Backbend Double, 2018, acrylic, charcoal, oil pastel, and foil on newspaper mounted on canvas

Derek Fordjour creates art that explores themes of race and identity, often incorporating various media on canvas.

Rhonda Brown

Rhonda Brown, Royal II, 2020, acrylic on canvas

An artist and art world professional, Rhonda Brown specializes in advising individuals and institutions on building thoughtful art collections with a focus on Black artists.

Cey Adams

Cey Adams, Paramount/Kool-Aid, 2015, handmade fiber paper, magazines, and acrylic on canvas

Cey Adams emerged from the downtown graffiti movement of the 80s and became the founding Creative Director at Def Jam Recordings, shaping the visual culture of Hip-Hop.

Violeta Sofia

Violeta Sofia, Dutch Master, 2024, mixed media

Award-winning artist, photographer, and activist Violeta Sofia is deeply influenced by her multicultural upbringing, explores themes of identity, diversity, and human connection with a focus on female inclusivity and representation.

Interview: Lourdes Martin, Journalist

In our inaugural micro-interview, journalist Lourdes Martin reflects on how her popular blog, Please, Do Tell, evolved from personal travel reflections into a powerful platform focused on human rights. Martin shares how intentional travel can offer a vital creative and emotional reset, uncovering the deeper stories that objects can tell about the world.

New York-based journalist Lourdes Martin reflects on the recent editorial pivot in her popular blog, Please, Do Tell, which launched as a collection of personal travel reflections and has now evolved into a powerful platform with a sharp focus on human rights. Martin also shares how she navigates the complexities of global issues, details the transformative power of intentional travel, and uncovers the objects that can tell a deeper story about the world.

Can you share the story behind Please, Do Tell? What inspired the launch initially?

After earning my degree in International Human Rights, I found myself emotionally drained. The work was important—deeply meaningful—but I realized I didn’t have the bandwidth to stay immersed in such heavy issues day in and day out. I needed space to breathe, to create, and to reconnect with a different part of myself. The blog began as a personal space for reflection and writing, but it quickly evolved into something larger: a place where others could slow down with me and discover people and places around the world through a more thoughtful lens.

It wasn’t about fast itineraries or bucket lists—it was about staying long enough to learn a neighborhood’s rhythm, to meet locals, and to find meaning in the quieter moments of travel. Please, Do Tell became a way to share not just where I was going, but how I was seeing—and who I was meeting along the way. Over time, it grew into a community that valued connection, curiosity, and the belief that travel, when undertaken slowly and with intention, has the power to restore and transform.

The editorial mission of Please, Do Tell has shifted in our current political landscape to train a lens on human rights. Can you explain your thought process with that shift and how you plan to build on it going forward?

Please, Do Tell has always been rooted in storytelling that bridges place, identity, and culture. But lately, I’ve felt a strong pull back to my roots in international human rights—I hold an M.S. in Global Affairs with a focus on human rights, and that lens has always shaped how I see the world. Maybe it’s because of what’s unfolding here in the U.S. and around the world—the erosion of democracy, the rise in authoritarianism, the targeting of migrants and marginalized communities.

It no longer feels sufficient to tell beautiful travel stories without also reckoning with the political and human realities shaping those places. The stories I want to tell now are still grounded in curiosity and connection, but with a sharper focus on justice, resilience, and what it means to belong. For now, I plan to continue writing about these issues via my newsletter on Substack and for other media outlets.

For many people in the U.S., it can feel like we’re living in the upside-down. What are your thoughts on how travel can alleviate some of the unease and perhaps even provide a bit of emotional and creative reset?

One of the most healing things about travel, for me, is how it pulls you out of your everyday bubble and drops you into a much bigger world. When you’re stuck in the same routines and the constant noise of the news cycle, it’s easy to forget that other ways of living exist. But stepping into a new place—hearing a different language, observing the rhythm of someone else’s day, noticing what’s sacred or ordinary in another culture—can shift something in you.

It reminds you that your reality isn’t the only one. That the world is layered and full of beauty, even in hard times. That perspective alone can be grounding, even healing. It creates space for awe. And sometimes, that’s exactly what we need to feel like ourselves again. Last summer, my husband and I spent seven weeks in Mexico City, and I came home completely reset—emotionally, creatively, spiritually. I felt refilled. Reoriented. The noise was still there, but I felt lighter.

The theme of this issue is Objects– are there things beyond the basics that you always travel with?

Beyond the basics, I always pack a notebook– it’s my way of catching whatever rises to the surface while I travel. Thoughts, passing observations, fragments of conversation… things I might not even notice at home suddenly feel rich with meaning. Being in a new place always stirs something loose in me, and writing helps me sort through it. The notebook becomes a kind of companion—part memory-keeper, part sounding board. Travel has also been a powerful creative trigger. New surroundings, new smells, new textures—they always spark fresh ideas.

Your blog used to include a well-edited shop called Recuerdos, where you featured items from around the globe. Besides typical souvenirs, what objects do you think can more deeply tell a story about the people of a country?

Yes, I launched Recuerdos during the pandemic as a way to help people travel from home, through objects that tell a deeper story. Beyond typical souvenirs, I’ve always been drawn to things that carry the weight of daily life and memory. Souvenirs aren’t just keepsakes—they’re part of your travel story, a tangible way to revisit a place long after you’ve left.

A hand-embroidered pouch from Chiapas, a bar of chocolate made by Indigenous women in the highlands, saffron and spice blends from Afghan women reclaiming their livelihoods, a beeswax candle poured by Syrian refugees, or a clay cup shaped in the hills of Oaxaca—these aren’t just items. They carry scent, texture, and story. They remind us that even in the hardest circumstances, people create beauty. Every object holds a little resilience. A little soul.

Learn more about Lourdes and read her newsletter, Please Do Tell, here. Above, postcards from Martin’s journeys throughout Mexico.