Who Gets the Time to Create?

Creative work has always needed one thing more than anything else: time. Not the romantic kind that floats through glossy studio tours, but the real kind– the hours you fight for, protect, and stretch, the hours when your mind is clear enough to make something that didn’t exist before. And in 2025, time has quietly become the true measure of privilege in the creative world.

That’s why the conversation coming out of the UK feels so telling. There’s been a growing chorus of voices pointing out what many already knew: an alarming number of the country’s most visible young artists come from upper-class families. Not because they’re less talented, but because they’re the ones who can afford to spend years experimenting, drifting, refining. They have the safety net to take creative risks while others are working shifts, managing caretaking, or navigating the instability that makes risk impossible. In short, their parents are paying the bills while they are in studio.

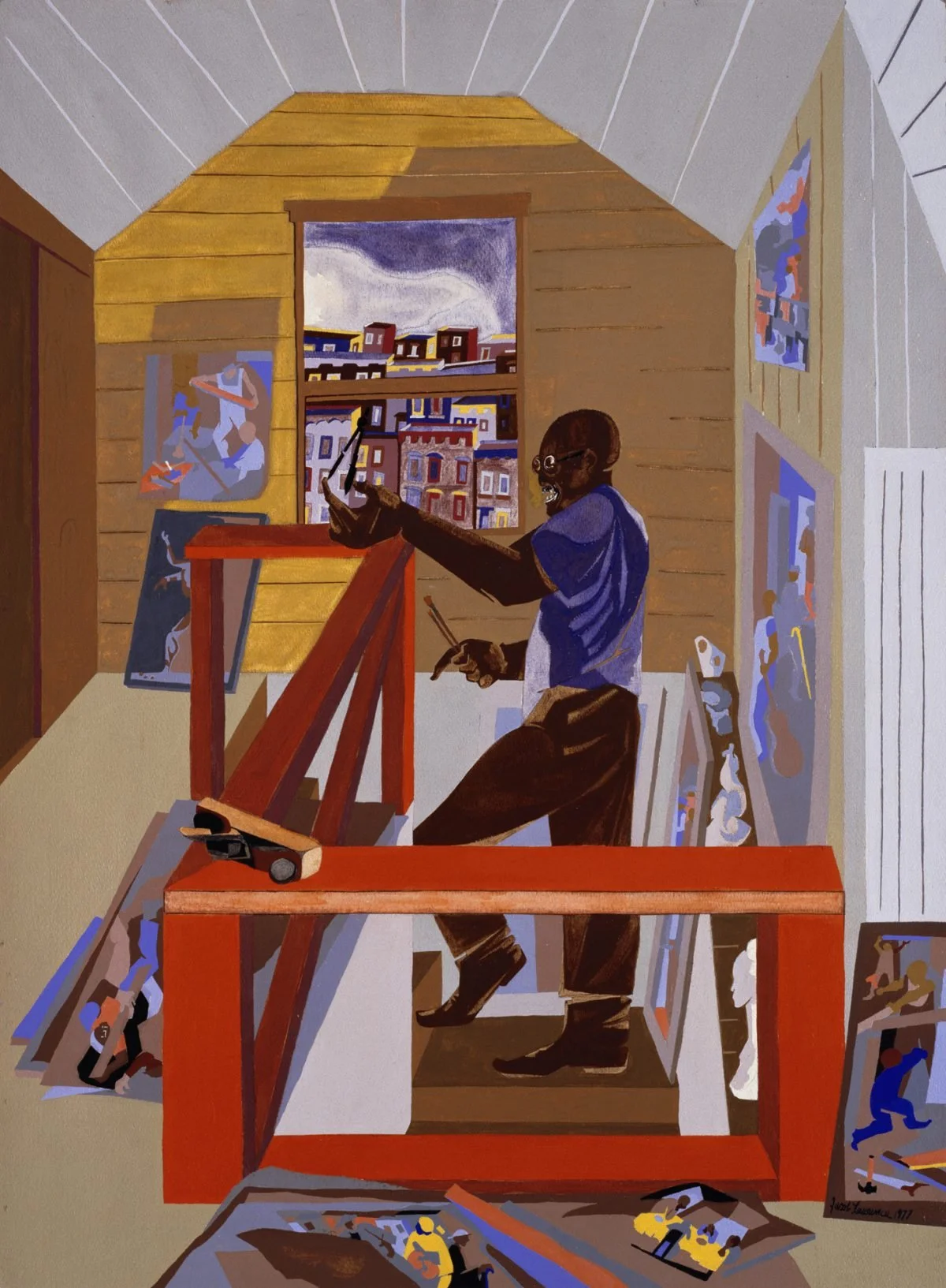

Across the Atlantic, the U.S. amplifies this dynamic. This country hasn’t meaningfully invested in artists at a federal level since the WPA, nearly a century ago, when creative labor was treated as necessary infrastructure. It’s always a bit jarring to be reminded that the government once subsidized the work of some of the giants of American early modern art. Since then, artists have been expected to bootstrap themselves into cultural relevance, often without stability, support, or time. Here, you either inherit spaciousness or you create in the margins of your exhaustion after you clock out.

And yet, this is where the story turns. Because if you listen closely, the most interesting work right now isn’t coming from the people with the most time; it’s coming from the ones who carved it out anyway. Working-class artists, immigrant artists, artists raising families, artists threading creativity through jobs, commutes, and late nights. People whose creative muscles are shaped not by comfort but by constraint, resourcefulness, and lived experience.

The future of culture is already being built from the ground up, by the people who were never invited into the “creative class” conversation. By artists who had to become their own institutions. By communities that have always produced the culture everyone else eventually catches up to, especially Black creatives and other marginalized communities.

But the uncomfortable truth remains: creativity takes time, and time is currently distributed the same way wealth is– unevenly, predictably, and with generational consequences.

So the real question isn’t whether working-class artists exist. They always have.

The question is: what would culture look like if they had the time they deserved?

If time weren’t a luxury item?

If creative risk wasn’t a class privilege?

If the next WPA wasn’t a memory but an intentional, renewed mandate?

Because the next era of creativity is already here– it’s just waiting for the world to make room for it.

image: The Studio, 1977, Jacob Lawrence, Gouache on paper